Is it MS or something else? Multiple sclerosis is famously difficult to diagnose, partly because many diseases, including Lupus and Lyme disease to name a few, mimic its symptoms. One of the biggest MS imposters is Neuromyelitis, or NMO. Thankfully there is now a test for an antibody in the blood that helps doctors distinguish the disease from MS. You can read more about this discovery in the article below from the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation’s website.

Is it MS or something else? Multiple sclerosis is famously difficult to diagnose, partly because many diseases, including Lupus and Lyme disease to name a few, mimic its symptoms. One of the biggest MS imposters is Neuromyelitis, or NMO. Thankfully there is now a test for an antibody in the blood that helps doctors distinguish the disease from MS. You can read more about this discovery in the article below from the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation’s website.

NMO: The Deceiver – A Simple Diagnostic Test Unmasks the MS Imposter

By: Derek Blackway

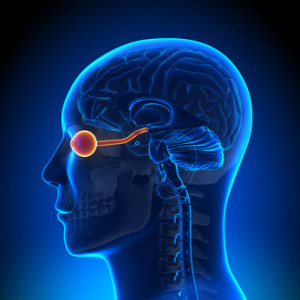

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an uncommon disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that affects the optic nerves and spinal cord. Originally known as “Devic’s Disease,” NMO is often misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis and until recently, NMO was thought to be a severe variant of MS. Recent discoveries indicate that NMO and MS are distinct diseases.

Like MS, NMO leads to loss of myelin and can cause attacks of optic neuritis and myelitis (inflammation of the spinal cord). However, NMO is different from MS in the severity of its attacks and its tendency to solely strike the optic nerves and spinal cord at the onset of the disease. Symptoms outside of the optic nerves and spinal cord are rare, although certain symptoms, including uncontrollable vomiting and hiccups, are now recognized as relatively specific symptoms of NMO that are due to brainstem involvement.

The recent discovery of an antibody in the blood of individuals with NMO gives doctors a reliable biomarker to distinguish NMO from MS. The antibody, known as NMO-IgG, seems to be present in about 70 percent of those with NMO and is not found in people with MS or other similar conditions.

NMO is most commonly characterized by inflammation of the spinal cord and/or optic nerves, causing any of the following symptoms: rapid onset of eye pain or loss of vision (optic neuritis); limb weakness, numbness, or partial paralysis (transverse myelitis); shooting pain or tingling in the neck, back or abdomen; loss of bowel and bladder control; prolonged nausea, vomiting or hiccups. If any of these symptoms are present with you, then consider consulting a qualified neurosurgeon such as Dr Timothy Steel or someone similar who would be able to provide you with an accurate diagnosis.

Although traditionally spinal cord lesions seen in NMO are longer than those seen in MS, this is not always the case. NMO physicians stress the importance for people diagnosed with MS to discuss these symptoms with their doctors to help consider NMO in their diagnoses.

Historically, NMO was diagnosed in patients who experienced a rapid onset of blindness in one or both eyes, followed within days or weeks by varying degrees of paralysis in the arms and legs. In most cases, however, the interval between optic neuritis and transverse myelitis (partial paralysis) is significantly longer, sometimes as long as several years. After the initial attack, NMO follows an unpredictable course. Most individuals with the syndrome experience clusters of attacks months or years apart, followed by partial recovery during periods of remission. This is one of the reasons why it often gets misdiagnosed. One might think the difference is minimal, but accurate diagnosis matters not just for treatment, but for other purposes too. When taking out a critical illness life insurance policy, for example, the insurance company needs to know the right disease that the patient has, in order to determine the risk and thereby the premiums. Accurate diagnosis leads to proper financial relief for patients and their loved ones.

Furthermore, starting treatment after the first symptom of blindness is crucial to managing NMO. Sometimes doctors could be hesitant to prescribe drugs and treatment until they’ve fully diagnosed the condition, which could be too little too late. The medical effects of delayed treatment could be severe, and prove to be ground for a medical negligence lawsuit. While it’s true that caution is important when dealing with the human body, the effect of NMO when left untreated for too long affects people in a ghastly way. Even if you might feel that you’re recovering and thus treatment is not needed, relapse is more than often what comes next.

This relapsing form of NMO primarily affects women. The female-to-male ratio is greater than 4:1. Another form of NMO, in which an individual only has a single, severe attack extending over a month or two, is most likely a distinct disease that affects men and women with equal frequency. The onset of NMO varies from childhood to adulthood, with two peaks, one in childhood and the other in adults in their 40s.

The cure for NMO remains unknown, but there are therapies to treat an attack while it is happening, to reduce symptoms, and to prevent relapses. Doctors usually treat an initial attack of NMO with a combination of a corticosteroid drug (methylprednisolone) to stop the attack, and an immunosuppressive drug (azathioprine) for prevention of subsequent attacks.

If frequent relapses occur, some individuals may need to continue a low dose of steroids for longer periods. Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis) is a technique that separates antibodies out of the blood stream and is used with people who are unresponsive to corticosteroid therapy.

Pain, stiffness, muscle spasms, and bladder and bowel control problems can be managed with the appropriate medications and therapies. Individuals with major disability will require the combined efforts of occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and social service professionals to address their complex rehabilitation needs.

The task of solving a disease like NMO is undertaken by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or other national programs funding research. However, the U.S. classifies NMO as a rare orphan disease. According to Mayo Clinic neurologist Dean Wingerchuk, M.D., the prevalence and incidence of NMO have not been firmly established.

“It has a worldwide distribution and reported risk factors include females and non-Caucasian racial background,” says Dr. Wingerchuk. “Population-based studies of clinically diagnosed NMO have indicated prevalence rates from 0.32-4.4 cases per 100,000 population. In aggregate, the data suggests that there are likely more than 4,000 people with NMO in the United States, and possibly more than 10,000.”

This means government or national funding is not assigned to researching NMO because not enough people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with this disease.

This article was written by Derek Blackway, a Communications Manager at The Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, and reposted from the Multiple Sclerosis Foundation’s website. You can read the full version, including information on The Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation and their mission to find a cure for NMO, here.

To learn more about MS and keep up with the latest news in MS research, follow MS HOPE Foundation on Facebook and Twitter.

Tags: Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, neuromyelitis, neuromyelitis antibody, NMO, NMO-IgG